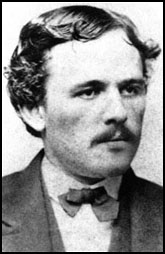

We were recently contacted by someone who was curious about Lew’s vote during the Lincoln conspirators trial. I’ve already emailed the inquirer directly, but I thought this would be a good time to talk more about Louis Weichmann, who was pivotal in the conspirators trial.

Louis was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to German parents in 1842. At the age of seventeen, intending to study for the priesthood, he entered St. Charles’ Seminary in Maryland and there met and became close friends with John Surratt—a friendship that would have lifelong implications. In 1862, both Louis and Surratt left the seminary without obtaining their degrees. Louis moved to Washington, where in 1864 he became a clerk in the War Department. His friend John Surratt took another path, becoming a courier for the Confederacy. Louis took a room in Mary Surratt’s boarding house, which brought him into contact with the major conspirators in the Lincoln plot.

Louis was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to German parents in 1842. At the age of seventeen, intending to study for the priesthood, he entered St. Charles’ Seminary in Maryland and there met and became close friends with John Surratt—a friendship that would have lifelong implications. In 1862, both Louis and Surratt left the seminary without obtaining their degrees. Louis moved to Washington, where in 1864 he became a clerk in the War Department. His friend John Surratt took another path, becoming a courier for the Confederacy. Louis took a room in Mary Surratt’s boarding house, which brought him into contact with the major conspirators in the Lincoln plot.

Louis’ testimony in the trial placed John Wilkes Booth, David Herold, Lewis Payne, George Atzerodt, and John Surratt at the Surratt boarding house with great regularity. He further testified that on April 14, 1865, the day Lincoln was shot, he had accompanied Mrs. Surratt to her rural property where, unbeknownst to him, she delivered items that John Wilkes Booth retrieved during his flight after the assassination. Louis also linked Dr. Samuel Mudd to events surrounding the conspiracy.

Louis’ testimony proved instrumental, but it was not without controversy. Augustus Howell, a blockade runner, claimed Louis had provided classified information to the Confederacy obtained from his Department of War job. While the accusations were never proven, there was concern about Louis’ possible involvement. He had originally been arrested as one of the conspirators, and Secretary of War Stanton was rumored to have put pressure on Louis to produce conviction-worthy testimony.

Lew wrote that Louis “had been innocently involved in the schemes of the conspirators, and although the Surratts were his personal friends, he was forced to appear and testify when subpoenaed. He realized deeply the sanctity of the oath he had taken to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, and his testimony could not be confused or shaken in the slightest detail.”

In the days before the hangings, Louis was deeply troubled by the role he played in Mary Surratt’s conviction. Mary was the first woman tried and executed for a capital crime by the United States and her death left many with a poor opinion of Louis. Lew was not among them. As Gail Stephens points out in her book, Shadow of Shiloh, “Though Wallace never discussed his vote, there are clues to his feelings. Five members of the commission petitioned President Andrew Johnson to commute Mary Surratt’s sentence to life in prison on account of her age and sex. Wallace did not join them.”

Louis continued working for the federal government until Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected president. His brother and two of his sisters had moved to Anderson, Indiana, and at that point Louis moved to be near them. He worked briefly at a business school and when that closed, he opened his own business school.

But the cloud of his relationship with the Surratts continued. While his siblings supported him, many in the community felt he was smarmy and self-serving, nervous and peculiar. He would never stand with his back to the door and rarely left the house after dark or alone.

Public doubt about his testimony lingered throughout Louis’s life. Because of strong anti-Catholic sentiment in 19th century America, the faith he shared with the Surratts raised the issue of a “Catholic conspiracy” surrounding Lincoln’s assassination. In an effort to clear his name, Louis wrote his autobiography, A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and of the Conspiracy of 1865.

Toward the end of his life, Louis swore out an affidavit reaffirming all of his testimony was true. He died just a few days later on June 5, 1902. Even though he was buried 112 years ago, and in spite of the positive comments made by Lew Wallace, doubts about Louis Weichmann’s role in the Lincoln assassination linger on.

Sources:

History: Louis Weichmann, Anderson’s connection to the Lincoln Assassination. Beth Olijace, Anderson Public Library, February 2, 2010

2 thoughts on “People Lew Knew: Louis Weichmann, Witness to Conspiracy”

It’s diffucult to know the truth if was involved in the assesination or not, he only knew and he took it until his grave. Really interesting