One hundred and fifty years ago in April of 1862, the Battle of Shiloh raged in Tennessee. Considered one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, it saw its share of men who would go down in history. Some of these men would be remembered for their valor that day and some for accomplishments later in life. Lew Wallace was one of these men. He is remembered for a number of reasons, but perhaps most famously for his writing of Ben-Hur. Wallace was not the only survivor of Shiloh who would make his mark with writing. At least two other famous authors survived Shiloh, Ambrose Bierce and Henry Morton Stanley.

Bierce – His Early Life

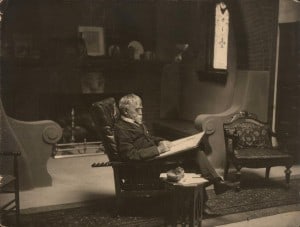

Ambrose Bierce was an American editorialist, journalist, short story writer, fabulist, and satirist who is probably best-known for his short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” and his satirical lexicon The Devil’s Dictionary. His vehemence as a critic, his motto “Nothing matters,” and the sardonic view of human nature that infused his work, all earned him the nickname “Bitter Bierce.” Born in Ohio Bierce in 1842, Bierce grew up in Warsaw (Kosciusko County) Indiana. Although his parents were poor, his mother was a descendant of William Bradford. Both his mother and father loved literature and instilled a love of books in their son. Ambrose and his nine siblings all had names beginning with the letter “A.”

Ambrose was 19 when the Civil War broke out. He quickly enlisted in the 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment. Bierce fought in a number of engagements, including Shiloh. In June of 1864, he received a head wound at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain and spent months recovering. He returned to the field but left the military in January of 1865. In 1866, he rejoined the army for a brief stint with a former commander who was inspecting military operations out west. With this tour he ended up in San Francisco and left the army as a brevet major.

Post-War Life

Bierce stayed in San Francisco for several of years writing for a number of newspapers, often covering the local crime scene. From 1872 to 1875 he lived in London before returning to San Francisco in the late 1870s. He tried a number of different careers but always returned to writing and by the late 1880s, he was writing a column called “Prattle” and had become the first regular columnist and editorialist to be employed by William Randolph Hearst. He became one of the most important columnists in the West and stayed with the Hearst newspaper empire until 1906. For a time Bierce was posted in Washington, D.C. where he covered the behind the scenes activities of politicians and lobbyists, exposing deals and legislation that often embarrassed the participants.

Beyond his editorials and columns, his short stories are regarded as among the best of the 19th century. He wrote realistically of the terrible things he had seen in the war in stories such as “What I Saw of Shiloh,” “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” “The Boarded Window,” “Killed at Resaca,” and “Chickamauga.”

Beyond his Owl Creek story, Bierce is also remembered for The Devil’s Dictionary. This work satirized many of the celebrities of his day, including Robert Ingersoll, the agnostic who spurred Lew Wallace to rework a story on the Three Wise Men that ultimately became Ben-Hur. In The Devil’s Dictionary, Bierce included his version of the Ten Commandments, in which the second commandment is, “No images nor idols make/for Robert Ingersoll to break.”

Marriage and Disappearance

Bierce married and fathered three children. However, his two sons died before him. After many years of marriage, he divorced his wife. In 1913, Bierce left his home in Washington, D.C., for a tour of the Civil War battlefields where he fought. He traveled on to Louisiana and Texas. After that, some historians think he crossed the border into Mexico to join Pancho Villa’s army as an observer. It is purported that he wrote a letter on December 26, 1913 to a friend, indicating that he was with Villa’s army and would be leaving the next day for a destination unknown. He vanished and was never heard from again.

Henry Morton Stanley

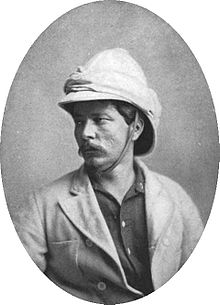

Another man who survived Shiloh went on to have success as a writer, but became most famous for finding someone the world thought had vanished! Henry Morton Stanley became one of the most quoted men of the 19th century after asking: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Henry Morton Stanley was born in Wales. His parents were likely unmarried and his father, believed to be a man named Rowlands, died within days of his birth. He lived with his grandfather for several years until the grandfather died.

After passing through the homes of a few relatives, young Henry ended up in a workhouse for the poor. He stayed in the workhouse until age 15. For a time, his mother and two brothers also lived in the workhouse; however, because of their years apart, he didn’t recognize them. Henry completed an elementary education and for a short time worked as a teacher. In 1859, at the age of 18, he sailed to America and jumped ship in New Orleans. At that point fate stepped in to change the young man’s life.

He happened upon a man named Henry Hope Stanley, sitting in front of his store in New Orleans. The young Welshman, hoping for a job, asked Stanley if he needed any help. Stanley did need help and a close relationship developed. The childless store keeper ultimately adopted young Rowlands. Henry changed his name to Henry Morton Stanley and did his best to drop his accent and deny his ancestry.

Stanley’s Civil War Service

Stanley reluctantly fought in the Civil War as a Confederate and saw action at Shiloh, where he was captured. When released from the prison camp in June of 1862, he joined the Union Army. He was discharged 18 days later due to illness. In 1864 he joined the Union Navy, where he served as a record keeper. This job led to a freelance writing career. In February of 1865, young Stanley, having served in the Confederate Army, the Union Army, and the Union Navy, decided to jump ship in an effort to find adventure!

Stanley began a career as a journalist and quickly undertook an expedition to the Ottoman Empire. Captured, he spent time in a prison before talking his way out of jail. Not satisfied with getting out of prison, he also succeeded in getting restitution for damage to his expedition equipment!

Newspaper Career

Immediately after returning from the Middle East in 1867, Stanley took a position with Colonel Samuel Forster Tappan of the Indian Peace Commission. Stanley served as a correspondent to cover the work of the Commission for several newspapers. Stanley’s exploits and direct writing style impressed James Gordon Bennett, founder of the New York Herald. Bennett hired Stanley as one of the Herald’s overseas correspondents. In 1869, Bennett’s son instructed Stanley to find Scottish missionary and explorer David Livingstone. Livingstone had vanished somewhere in Africa.

According to Stanley’s account, he asked James Gordon Bennett, Jr., how much he could spend. The reply (according to Stanley) was “Draw £1,000 now, and when you have gone through that, draw another £1,000, and when that is spent, draw another £1,000, and when you have finished that, draw another £1,000, and so on — BUT FIND LIVINGSTONE!” In actuality, Stanley lobbied his employer for several years to mount this expedition, which he hoped would lead to fame and fortune.

Stanley and Africa

In March of 1871, Stanley traveled to Africa and began an exhausting expedition through unchartered jungles. As the group of more than 200 travelled through the Congo, pack animals, porters, and associates got sick and some died. On November 10, on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, he found Livingstone and (reportedly) greeted him with the famous line. Together the two men explored more of the region. The New York Herald chronicled the expedition and upon his return, Stanley wrote a well received book about his exploits in Africa. This book did, in fact, offer Stanley some of the financial security he hoped for.

This was not Stanley’s last trip to Africa. In another financed expedition, he sought to find the source of the River Congo and follow it to the sea. This effort lasted 999 days and of the 356 people who started the trip only 114 survived with Stanley being the only European still alive at the end. This trip too was chronicled in a successful book. Stanley led other expeditions in Africa, some of them tainted by controversy. He returned to England, served in Parliament and was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1899, in recognition of his service to the British Empire in Africa. Stanley died in 1904.

Two Days in April

While it’s not recorded whether or not Lew Wallace, Ambrose Bierce, or Henry Stanley ever met on the battlefield at Shiloh, it is certain that the two days they spent there in April of 1862 changed their lives. Each of these men experienced war differently, but because of their service, opportunities opened up and each in his own way seized the moments and adventures they were offered. As Wallace wrote at the beginning of the Civil War: “May a man tell what he can do until he tries?”